How social media is ‘supercharging’ conspiracy theories

Clip: 3/23/2025 | 7m 16sVideo has Closed Captions

How online misinformation is ‘supercharging’ conspiracy theories

Can conspiracy theorists be shaken from their firm — and unsubstantiated — beliefs? Podcaster Zach Mack wanted to find out, so he turned to someone he’s debated about conspiracies for years: his father. He tells what happened in “Alternate Realties,” a three-part podcast from NPR. Mack and science writer David Robert Grimes join John Yang to discuss.

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...

How social media is ‘supercharging’ conspiracy theories

Clip: 3/23/2025 | 7m 16sVideo has Closed Captions

Can conspiracy theorists be shaken from their firm — and unsubstantiated — beliefs? Podcaster Zach Mack wanted to find out, so he turned to someone he’s debated about conspiracies for years: his father. He tells what happened in “Alternate Realties,” a three-part podcast from NPR. Mack and science writer David Robert Grimes join John Yang to discuss.

How to Watch PBS News Hour

PBS News Hour is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipJOHN YANG: This past week saw the release of a trove of documents related to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, a subject that's long been fertile ground for conspiracy theories.

Other favorite topics include beliefs that the moon landing, the 9/11 attacks and the January 6th assault on the Capitol were all staged.

Podcaster Zach Mack wanted to see if conspiracy theorists could be shaken from their firm but unsubstantiated beliefs.

So he turned to someone he's debated about conspiracies for years, his father.

Mack tells what happened in a three part podcast from NPR called Alternate Realities.

This clip begins with Mack talking with members of his family about his father.

ZACH MACK, Podcaster: This is a story about my dad, but it's really a story about what he believes and how his beliefs are impacting our family.

WOMAN: We've been married 40 years.

It's very hard to walk away from.

I want him to fundamentally change who he is and be a different person.

MAN: How can I halfway believe what I believe?

JOHN YANG: Zach Mack joins us now along with David Robert Grimes.

He's a science writer.

He wrote a book called "Good Thinking: Why Flawed Logic Puts Us all at Risk and How Critical Thinking Could Save the World."

Zach, I want to play another clip of your father sharing his beliefs.

MAN: They're going to shut us down because of this emp.

All the supply lines are going to be disrupted.

So there will be a one world government with a one world currency.

I think the Biden has probably three or four maybe more body doubles.

Obama will be found guilty of treason.

JOHN YANG: Zach, has he always believed things like this for as long as you can remember?

ZACH MACK: Kind of not exactly.

It's been a long time coming.

He grew up in a household that was very distrusting of vaccines and really sort of skeptical of major institutions like education and the health, you know, health organizations.

And then in the last maybe four or five years, really since the pandemic, he's gotten really into like just really out there conspiracies.

But you've seen that slow ramp up.

JOHN YANG: David, you've written a lot about how people come to these false conclusions.

Tell us how that happens, how that works.

And we heard Zach's father, their conspiracy theories from the right.

Does it matter which where they come from, right or left?

DAVID ROBERT GRIMES, Author, "Good Thinking": Not necessarily.

What's, what's really interesting about this is it's a really good example of what the philosopher W.V.

Quine called "Our Web of Beliefs."

We find that with conspiracy theorists they tend to hold multiple, often conflicting beliefs.

And the idea of the web of belief is that if you pull on the thread of one belief, for example, if you find able to accept there's a big conspiracy about vaccination, which of course there is not.

But if you can accept that, it makes it easier to think that there's conspiracies about other things.

So beliefs pull onto beliefs.

That's a very common thing.

JOHN YANG: We see you talk about these sort of how these things start.

Does our current media environment contribute to that, do you think?

Do you think?

DAVID ROBERT GRIMES: Absolutely.

And, look, there's always been conspiracy theories.

They've existed as long as humans have recorded history.

But what we've seen, and particularly since the Pandemic is we've seen a supercharging of these many years ago.

If you walked in with a, an outlandish belief and you voice that in polite company, someone would probably challenge you on it.

Now, if I go online, I can find communities of people that not only validate my belief, they will amplify it.

At times when things are uncertain or people are afraid, conspiracy theories, they proliferate more wildly.

And the pandemic was the first thing, the first pandemic we'd ever had during the age of instant communication.

And I think we're still feeling the reverberations of that five years on.

JOHN YANG: Zach, I suspect a lot of families go through what you go through with your father, but they don't invite strangers to come in and listen.

How was doing this podcast?

How was it for you and for your family?

ZACH MACK: Yeah, for me, it was incredibly emotionally difficult.

I'm not going to lie to you about that.

I'm not used to documenting myself or my family, so that part was challenging.

But it was much easier because everyone in the family was on board.

Everyone gave their permission.

They pledged their full support.

They were at times really excited about the project.

So I did have their support.

But, yeah, it's just difficult to report on your family, especially as it's sort of falling apart in real time.

JOHN YANG: Falling apart.

But we heard you talking to your mother and your sister in the clip, in the introduction.

ZACH MACK: Yeah.

JOHN YANG: Has your father always been sort of a person alone on this in your family?

ZACH MACH: Yeah, yeah.

He's sort of the lone Christian conservative in our household.

My mother is like a very liberal Jewish woman.

We grew up in the Bay Area, so it's a pretty liberal place.

My sister and myself sort of fall along the lines.

We're much more like left leaning in our beliefs.

So he's always been a little bit of the odd man out.

And now that he's become increasingly interested in conspiracies, he's like really sort of isolated himself.

JOHN YANG: David, I want to play a little clip of an argument that Zach and his father had.

MAN: It's called denying us freedom of speech.

ZACH MACK: No, no.

MAN: It's called denying us freedom of speech.

ZACH MACH: It's misinformation.

MAN: No.

Who gets the right to label it misinformation?

JOHN YANG: Can people be shaken from their beliefs?

And how would you suggest people go about it?

DAVID ROBERT GRIMES: Yes, but there's a lot of caveats to that.

It partially, it's a function of how deep down the rabbit hole people have gone.

If people are, you know, very early in that stage as they've been exposed to material and maybe they have some questions, that's a very fruitful time for, you know, collaboration where you can have discussions.

And I always say discussions are far more important than debates.

You never change anyone else's mind.

You simply give them the tools to do it themselves.

And you rarely get that from a adversarial format.

But it's very frustrating and it's very easy to get sucked into that.

The other thing is people.

You have to understand why people have been drawn to their different beliefs.

For example, we know aversion to randomness and fear of the unknown and the lack of epistemic certainty.

These are things that draw people towards conspiracy theories.

They're trying to explain the world around them, in that case giving them a better alternative.

Explaining why scientists or experts think something different can be very useful.

The other thing is you have a distrust of authority, which I think Zach's father would have shown for some time, where people who are inherently distrustful of certain forms of authority can be very easily brought to distrust further forms of authority or find an alternative belief system or authority system.

So understanding where people are coming from is really, really important, but really, really difficult.

JOHN YANG: Zach Mack and David Robert Grimes, thank you both very much.

ZACH MACK: Thanks for having me.

DAVID ROBERT GRIMES: Thank you for having me.

Gaza children ‘deeply traumatized’ as ceasefire breaks down

Video has Closed Captions

Children in Gaza ‘deeply traumatized’ as Israel expands military operations again (4m 46s)

News Wrap: Russian strikes across Ukraine kill at least 7

Video has Closed Captions

News Wrap: Russian drone strikes across Ukraine kill at least 7 people (2m 27s)

What Kenya is doing to create more open spaces for wildlife

Video has Closed Captions

How wildlife corridors can support Africa’s iconic animals (2m 52s)

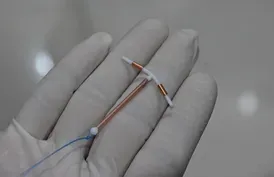

Why IUD insertions are painful for many and what can be done

Video has Closed Captions

Why IUD insertions are painful for many patients and what can be done better (6m 6s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMajor corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...