Finding Your Roots

Fighters

Season 8 Episode 6 | 49m 54sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

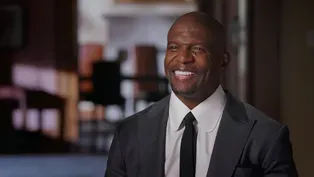

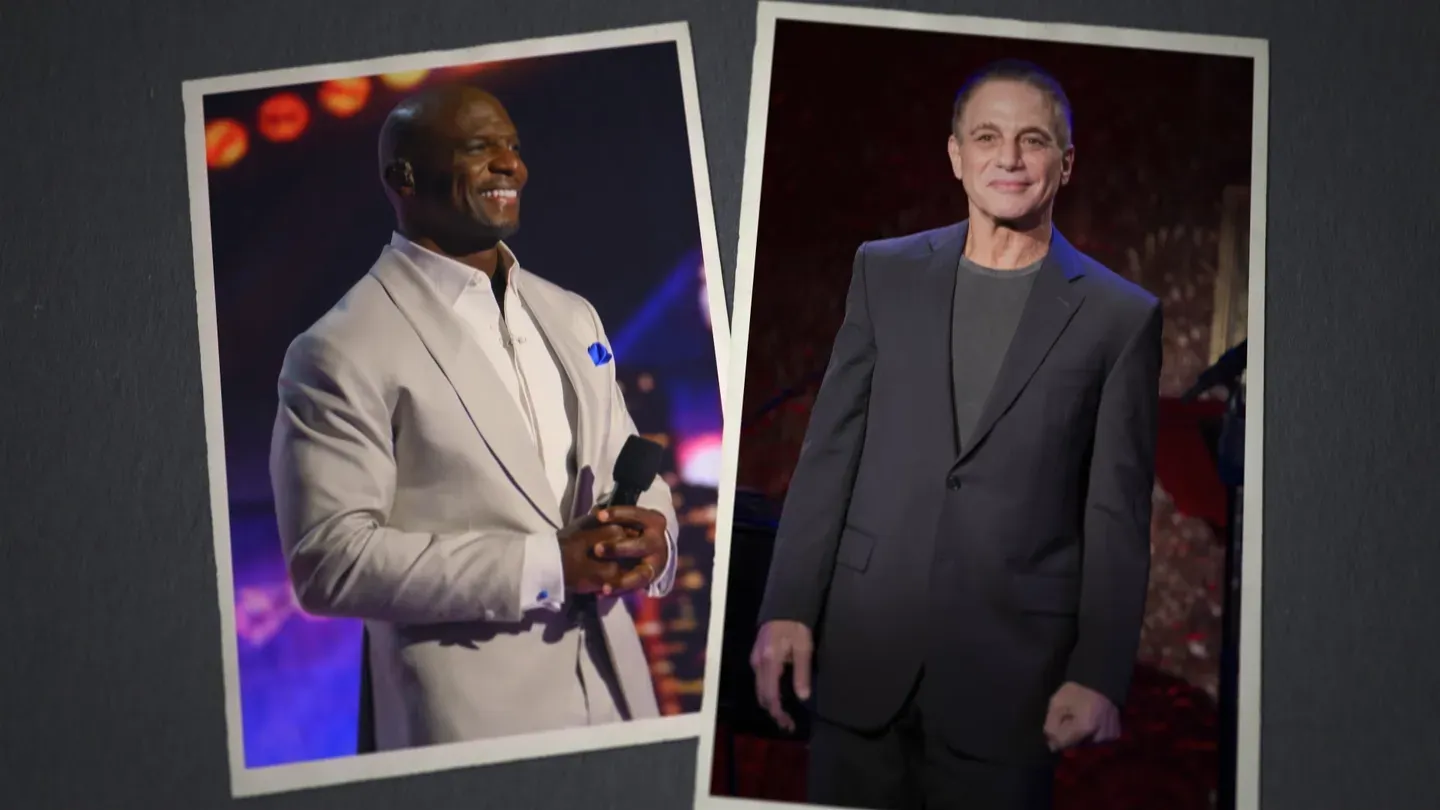

Terry Crews and Tony Danza find they aren’t the first in their families to beat the odds.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. sits down with Terry Crews and Tony Danza, both guests who overcame adversity, to discover they aren’t the first in their families to beat the odds through sheer force of will.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Fighters

Season 8 Episode 6 | 49m 54sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. sits down with Terry Crews and Tony Danza, both guests who overcame adversity, to discover they aren’t the first in their families to beat the odds through sheer force of will.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ GATES: Terry Crews has a story that defies all expectations.

He's a superstar actor, pitch-man, and author...

But he has absolutely no training in any of these fields.

He is entirely a self-creation... And that self was formed in the most unlikely of places... Terry was raised in Flint, Michigan in a home that was marked by intense conflict...

Circumstances that would have crushed most children.

CREWS: My father was addicted to alcohol.

GATES: Uh-huh.

CREWS: And my mother was addicted to religion.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: Which made a very, very caustic mix in our household.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: I mean, there were I, I'll be honest with you right here, I mean, I wet the bed until I was 15 years old because I did not know what was going to happen every night.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: I'd wake up to screaming, fights, glass breaking.

GATES: Oh.

CREWS: And I said, "I gotta find a, a way out" and sports was gonna be my way.

GATES: For Terry, "sports" meant football, and that posed a daunting challenge.

Even the most talented athletes stand very little chance of making it in the NFL.

But Terry beat the odds.

In 1991, he was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams and went on to play for three different teams over the next six years.

Then he faced a new challenge... CREWS: When I was done in 1997, we went broke.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: Promptly went broke.

And I, my attitude of being this, this, "I am a man, I'm a football player," and the whole thing, I wouldn't get a job.

And finally, when things got so rough we were digging in the couches for change, I decided... Actually, my wife told me, "Go get a job."

And I ended up sweeping floors.

And I started to sweep.

I was like, "Let me get these corners.

Let me get this a little better."

And I would get $8 an hour.

And I...

They gave me $64 cash.

And I had to pay my taxes right then and there.

I had $48.

I went home.

I gave my wife 20.

I put 20 in the gas tank.

And I had $8 in my hand that I didn't have yesterday.

I said, "I'll never be broke again."

GATES: Terry's tireless work ethic, and his remarkably positive attitude, would prove to be his salvation.

Eventually, he landed a job as a security guard on a film set where his talents were noticed, launching a second career that was even more improbable than his first... And now, looking back over a life marked by titanic ups and downs, Terry not only relishes his success but he's come to understand his parents, as well as his troubled childhood, with what can only be described as wisdom.

CREWS: My mother was doing the best she could with what she had, with what she knew.

Um, it-it's kind of like a saying that we have in the entertainment industry.

Like, there really are no villains.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: There are just people trying to get what they want.

You know?

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: It's, it's, I-I mean, that goes for my father too.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: He, he was doing what he knew to do.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: And if... Usually, if you know better, you do better.

GATES: Because, in the end, you have a choice.

CREWS: That's it.

You have a choice.

GATES: My second guest is the beloved actor Tony Danza.

A star of stage and screen for more than four decades... Tony came to fame in 1978 in the hit sitcom "Taxi" playing a Brooklyn-born boxer turned cab driver.

A tough-talker with a soft heart.

The role fit Tony to a tee.

Tony grew up in east New York, one of Brooklyn's roughest neighborhoods and was fundamentally shaped by the experience.

DANZA: I was small.

And unfortunately in Brooklyn when you're small you've got to fight.

You've got to fight a lot and so I was in a lot of street fights.

My father, I came home one day, I'll never forget it, I came home one day crying.

GATES: Mmm-hmm.

DANZA: He said to me, "I'm going to show you how to throw a right hand" and he showed me how to drop my shoulder and just throw a right hand.

So the next day, I was out getting bullied, somebody picked on me and I threw a right hand.

I hit the kid in the nose, and his nose bled and everybody in the place was like holy mackerel, look at that.

GATES: We got Muhammed Ali.

DANZA: Then, unfortunately, it became something that I kind of liked.

GATES: Much like Terry Crews, Tony came to see his athletic ability as his ticket to a better life...

Though he went to college and studied to be a teacher, by the time he was early 20s, he was boxing professionally, with decidedly mixed results.

DANZA: I could punch.

GATES: Really?

DANZA: I could really punch.

I wasn't much defense.

I had some skills, but I could bang.

If I hit you.

I used to miss guys and knock them out.

I mean it was crazy.

I mean it.

I won, all the fights I won, I won by knockout.

All the fights I lost I lost by knock out.

The good news was if you had a dinner date afterwards you were never late.

GATES: So how did your parents feel about you turning professional boxer?

DANZA: They were sick.

My mother was like I cannot believe I work hard to get you to go to college and then you're going to do this.

But I, and I'll be honest with you, now I look back at it and what I put them through.

You know, they both saw me get knocked out.

GATES: That's tough.

DANZA: Just one of the worst feelings.

GATES: Happily, Tony, and his parents, were all in for a surprise.

In 1977, a talent scout noticed Tony at a gym...

Soon he was auditioning for roles in films, trying to nurture an acting career alongside his boxing.

And on one magical night, everything came together.

DANZA: I went to an open call for a gang picture in New York.

I remember a lot of feathers, I don't know why.

But anyway, I brought the poster from my, I was fighting at Prospect Hall, it was my first main event, had my picture.

It said "Tough Tony Danza, Brooklyn's Knockout Artist."

And when I finished reading, it was Larry Gordon, Walter Hill, and uh, and uh, and Joel Silver.

I mean the big action movie guys, and it was at the end of a long conference table.

They were all sitting over there, and I read and they said thank you very much like they always do at these auditions.

Thank you very much.

When they said thank you very much, they said, hey, by the way, you really want to see a warrior and I unfurled the poster and I said come see me fight.

GATES: That's a good move.

DANZA: They said, "Wait a minute, you're a fighter?"

I said, "Yeah."

So they came to see me fight.

GATES: No.

DANZA: Yeah.

This whole bunch of Hollywood people came to this fight in Prospect Hall in Brooklyn.

I was the main event.

They sit through five boring fights.

It was a terrible card.

I remember it was just a horrible card.

But I knocked the guy out and into the front row in like 40 seconds or something.

I'll never forget, I was walking around the ring and I saw Larry Gordon, we made eye contact.

He went, "That's the greatest audition I've ever seen."

GATES: My two guests have both reinvented themselves through a combination of hard work and personal strength...

It was time to introduce them to ancestors who shared those traits.

We started with Tony Danza... Tony knew that his paternal grandparents, Anthony and Jennie Iadanza, had emigrated from Italy to the United States in the early 20th century.

In fact, Tony told me that their story was central to his identity...

But, as it turns out, he didn't have the full story.

In the 1930 census, we found Anthony and Jennie in Brooklyn, raising seven children together.

But when we jumped back twenty-five years, to the 1905 census for New York, we found Anthony in the same neighborhood, married to a woman named "Josephine".

GATES: Ever hear of her?

Well, Tony, our research indicates that your grandfather was married once before.

DANZA: Is that right?

GATES: Yes.

Your grandfather was married once before he married your grandmother Jennie, and we believe that his first wife Josephine likely died sometime after that census was taken in June 1905.

What's it like to learn that?

DANZA: Now, wait a minute.

Wait, wait, wait, wait.

So before Jennie arrives... GATES: Yeah.

He was married to another woman.

He was married to a woman named Josephine, who dies, and there's no recollection in your family?

DANZA: There's none.

Not a word.

GATES: This census would prove to be a gold mine for our research, not only revealing Tony's grandfather's early marriage but also providing us with insight into how he and his relatives carved out lives for themselves as immigrants in America.

On the entry for Anthony, we saw that he worked as a "helper"... And on the entry for a household just two doors away, we saw who he was helping... DANZA: "Iadanza, Matteo, occupation saloon keeper."

GATES: Matteo was your grandfather Anthony's older...

BOTH: Brother.

GATES: And your grandfather Anthony was a helper in the saloon.

DANZA: In the saloon.

GATES: In the bar, there you go.

And talk about history repeating itself, you worked as a bartender.

DANZA: That's true.

That's right.

I'll tell you the truth, that's where I learned to act when I was a bartender.

Bartending is where you learn how to act.

GATES: Oh, I'm sure.

Well, please turn the page.

DANZA: Oh, man.

They had a bar.

GATES: Yeah, how about that?

Tony, you're looking at the Brooklyn Standard Union.

DANZA: Oh my God, this is, holy mackerel.

GATES: This article was published February 14, 1905.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

DANZA: "Police Raid on Broadway House, The Standard Union.

The evidence pointed to the presence in the house of women of questionable character.

Detectives, made for the place again at number 2048 is a Raines Law Hotel owned by Matteo Iadanza.

There is a passageway in it leading to number 2046, which the police say is used as a disorderly house.

Detectives knocked on the door of number 2046 and Iadanza opened the door.

The Detective ran up from the rear and began a thorough search, which was rewarded by finding a trap door alongside a blind partition in a small middle room on the second floor.

The Detective opened the trap door, the officers lifted a young woman out of the pit and bundled her into the patrol wagon along with Iadanza.

Bail on the charge of keeping a disorderly house was fixed at $2,000."

GATES: So you understand... DANZA: I love this.

A baffling blind trap was found.

GATES: Isn't that amazing.

DANZA: That's unbelievable.

GATES: Tony's great-uncle Matteo was part of a fascinating moment in American history...

In 1896, New York state passed a liquor law, a predecessor to prohibition, banning the sale of alcohol on Sundays, except in hotels with at least ten rooms.

For saloon keepers like Matteo, this was a disaster.

Since they made such a large share of their income on Sundays, the only day of the week that most workers had off.

So they came up with an ingenious solution: converting their bars into fake hotels, with makeshift walls, and continuing to sell alcohol just like before... Often, it seems, they got into other illegal activity as well.

DANZA: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to learn that your family was part of this particular chapter in the history of America?

DANZA: Well, you know, it's strange because my father was really...

He reminds me of Robert De Niro in "A Bronx Tale".

GATES: Right.

DANZA: He was that kind of guy.

Stay away from that stuff because it was all over the neighborhood, you know.

You'd walk by the taxi stand and you'd see those guys and you know what they're doing.

So I'm surprised that this is in there.

I'm really and yet... GATES: And yet?

DANZA: Well, I think in Brooklyn in general there's always a bit of the bandit in everybody.

GATES: Matteo certainly embodied a good bit of the "bandit."

But setting aside his morals, he also played a very significant role in bringing Tony's family to America, as evidenced by the arrival of a ship from Naples, Italy on July 15, 1906...

Onboard was Tony's grandmother Jennie... DANZA: "Zarro, Giovanna, age: 18, single, occupation: dress maker.

Last Permanent Residence: Pietrelcina.

By Whom Passage Paid: Uncle.

Whether joining a relative: Uncle Matteo Iadanza, 2048 Broadway, Brooklyn, New York."

GATES: Isn't that cool?

DANZA: Wow.

GATES: So Tony, this marks the moment when your grandmother, Giovanna, Jennie, Zarro stepped foot on American soil.

And as you can see, her passage was paid by none other than Matteo Iadanza, your grandfather Anthony's brother, her future brother-in- law, the saloonkeeper.

What's it like to see that record?

DANZA: I guess he had the money.

GATES: He had the cash, baby.

DANZA: That's the first thing, you know.

GATES: And check this out.

The reason that Jennie referred to Matteo as her uncle was that actually Matteo was married to Jennie's aunt Rufana.

Did you know that?

DANZA: No.

This is all so, you know, pins and needles.

It's really, its spine-tingling.

It really is.

GATES: Well, we don't know if your grandfather Anthony was with his first wife Josephine when Jennie arrived in America.

All we know is that Jennie went to live at 2048 Broadway where the saloon was located with Matteo and Rufana.

And then eight months later on March 7, 1907, your grandparents got married.

DANZA: They got married.

GATES: Yeah.

DANZA: So Josephine, by then is probably... GATES: She's gone.

DANZA: Morte, yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

What's it like to learn this story?

DANZA: Man, I'm telling you.

We were saloon owners.

This is great.

GATES: You were tricking the law.

I like that.

DANZA: This is incredible.

GATES: The passenger list for the ship that brought Jennie to New York also gave us the name of her hometown: Pietrelcina, a village in the Campania region of southern Italy and the place where Tony's father's family had lived for centuries likely as subsistence farmers.

Indeed, we were able to map Tony's roots in the region back to at least the year 1774, giving name to five generations of his ancestors... DANZA: That's incredible.

GATES: Now, Tony, you're quite a restless guy.

You're constantly reinventing yourself.

What's it like for you to know that your ancestors stayed put in one place for so long?

DANZA: I just, it speaks to how people were at that time, I think, you know, and it also speaks to a way of life that probably was ongoing for many years and didn't change that much.

What also speaks to me though is that if you do go back this far and there is this roots and heritage in this place and yet they were so determined to get to America.

GATES: Absolutely, yeah.

DANZA: That really strikes me.

GATES: Probably motivated by poverty.

DANZA: Poverty.

There's something beautiful about seeing this.

It's just, it does really give you a different feeling about your place in the succession that's been going on since 1774.

GATES: Yeah.

DANZA: You know, it gives you this feeling of real...

Wait a minute, we've been here a long time.

Longer than I thought.

GATES: Much like Tony, Terry Crews was about to meet ancestors who overcame a formidable amount of adversity.

The story began with his maternal grandmother, a woman named Mary Ellen Walker.

Mary was born in rural Georgia but lived most of her life in Flint, Michigan where she played a pivotal role in Terry's childhood.

Growing up, he called her "mama' and Mary's love, support, and larger-than-life personality were among the brightest spots in Terry's turbulent youth.

CREWS: This was the thing.

My mother had me at 18.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: And she had my brother at 16.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: So she was almost a big sister.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: You know, and she didn't like us to call her "Mom."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: She got with us and we called her "Trish."

"Hey, Trish."

So she was almost like a big sister to us.

But Mama, however, Mama was... she was everything.

And one thing about Mama is that she had made her money.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: And she made her way and she worked like crazy.

She worked at AC Spark Plug.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: And this was the weird dynamic that was in our family is that my mother was always like, "You know, your grandmother got money."

But she just said, "She could be giving us some.

But she ain't doing it because she knows that..." She'd go into this whole thing.

And I kind of developed this attitude like, hey, Mama need to give us some money, you know.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: But when you look at what she accomplished.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: This, this woman from Georgia came all the way up here, made it happen for her family.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: Paid off a house... GATES: And paid off a house.

CREWS: And cars, went through a couple husbands.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: And survived.

GATES: Mary was, indeed, a survivor... Much like Terry, she'd endured a very challenging childhood and found stability in an unlikely place.

Sometime in the late 1930s, when she was still a teenager, Mary moved from Georgia to Flint, not to live with her parents, but to live with her maternal grandfather, a man named Edward Elbert, we found Mary in the 1940 census.

One of thirteen people in Edward's multi-generational household, which included four of his children, as well as a daughter-in-law... And he was also taking care of five of his grandchildren.

CREWS: Wow.

GATES: Including your grandmother.

Which of course raises a question.

Where were Mary's parents?

CREWS: Yeah.

GATES: Well, we aren't sure.

Mary's parents, your great-grandparents, were named Robert Walker and Leonora Elbert.

CREWS: Mm-hmm.

GATES: And we know very little about them.

We know that they were both born in Georgia and they were both born in the early 1900s.

But we can't find either of them in the 1940 census.

It seems they sent their children to live in Flint with their grandfather sometime between 1935 and 1940.

Did Mary ever talk about them?

CREWS: No, she didn't.

GATES: And think about this.

In 1940 your great-great-grandfather Edward was 69 years old and he was taking care of this enormous household.

CREWS: Wow.

GATES: Terry wondered how could Edward have possibly supported so many people.

The 1940 census indicated that he was a farmhand who owned his own home, but at that time, America was mired in the great depression and farmhands were making almost no money.

Things didn't quite add up until we discovered that Edward had some other occupations as well... GATES: Could you please turn the page?

CREWS: Whoo.

GATES: Terry, this is so cool.

This is an ad in a newspaper called "The Detroit Tribune".

CREWS: Oh.

GATES: Published on August 16th, 1941.

Would you please read what it says?

CREWS: What?

Okay.

"Edward Elbert.

Red Man's Emergency Wagon.

Hauling all kinds.

Sodding and cement work.

Hunting dogs for sale."

Oh my god.

He was a businessman.

GATES: He was a businessman.

CREWS: This is what I love.

Oh my goodness and you know I'm going to get a tee-shirt with this on it.

I'm going to bring this business back, I'm gonna tell you that.

GATES: Your great-great -grandfather was a super industrious hustler.

Not only was he working as a farmhand, he also did all kinds of handiwork on the side.

He's selling dogs, he's selling cement, he's hauling trash, he's doing lawn work, and he's taking out an ad for his services in a newspaper.

Did you have any idea that you had this entrepreneurial vein in your ancestral line?

CREWS: I had no idea.

I'm sorry, I'm just getting emotional.

This is...

I had no idea.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: Because all I do is think of new ideas.

GATES: Mmm-hmm, yeah.

CREWS: The new things and ways and new opportunities.

And I'm looking at, here he was doing the same thing.

GATES: You didn't invent it, you inherited it.

CREWS: That's right.

GATES: Edward's accomplishments are all the more impressive given what we discovered next...

In the 1870 census, we found Edward's father.

A man named Eddie or Ebb Elbert and his parents, George and Fannie Newsome, living in Sandersville, Georgia.

All were newly freed from slavery.

And as we set out to trace them back through time, we encountered a horrifying story.

In December of 1858, Fannie and five of her children were separated following the death of their owner.

GATES: Their family against their will, out of their control, was torn apart, ripped apart.

CREWS: First of all, I have five beautiful children.

I cannot imagine any of my babies being yanked and pulled out of my arms into some... And taken away into someone else's household.

I'd, I, I would never know where they went.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: And with no hope of seeing them again.

GATES: This is just in one day, one action.

CREWS: Can you imagine having your family separated and the generations all... And you... One day you saw your mom, and the next day she was gone forever.

GATES: She's gone.

CREWS: Oh, man.

I can't imagine.

GATES: It's, it's heart-wrenching.

CREWS: Incredible.

GATES: Fannie was about 32 years old when her owner's estate was divided.

At the time, her husband George was enslaved on a nearby property, owned by a planter named Hezekiah Newsome.

So, Fannie was now in danger of never seeing her husband, or some of her children again.

But, miraculously, that's not what happened.

In 1861, Fannie and two of her children were hired out to work on the Newsome plantation.

Reuniting the family, at least in part.

GATES: They didn't get sold down the river.

CREWS: Yes.

GATES: They were on, they, nearby, and they brought them back together by... CREWS: Wow.

GATES: Hiring them out for a nominal sum.

$25, which is $656 in 2020.

CREWS: Oh, oh.

GATES: So, what do you think this was like for your ancestors, after this three-year period?

CREWS: Oh.

GATES: On the one hand, it's a happy moment.

CREWS: Listen, I am... First of all, I'm jumping with joy right now, right?

I mean, the reunion had to be spectacular.

GATES: Yeah, isn't that cool?

CREWS: That is the coolest thing ever.

GATES: Back in the house again.

CREWS: In the midst of all this horror they get to be back together again.

GATES: Yeah, they get to be back together again.

CREWS: Wow.

GATES: This reunion was only the beginning.

Four years later, the end of the Civil War would bring an end to slavery, and Terry's ancestors would finally be free to live as they chose...

Returning to the 1870 census, we looked with fresh eyes at George and Fannie's household, seeing it now as evidence of how a family torn apart by slavery had pulled itself back together again... CREWS: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to know that your ancestors had such strong family bonds?

CREWS: This is beautiful.

It's beautiful.

GATES: They managed to create a family sometime in the mid-1840s and keep that family together and intact, so that five years after the Civil War, when the, the enumerator from the census came by, they were... CREWS: They were... GATES: All living together 30 years later.

CREWS: Man, this is a movie.

This is a movie.

GATES: It's true.

CREWS: No, it is.

GATES: And it's your story.

CREWS: This is a movie!

Think about this.

GATES: It's your story... CREWS: They were all split up, different homes, but, and they found a way to stick together.

GATES: We'd already revealed how Tony Danza's paternal ancestors made their way from Italy to America, via a Brooklyn saloon... Now, turning to his mother's roots, we uncovered a journey that was even more surprising...

The story begins with Tony's grandfather, Antonino Camisa, a legendary figure within his family.

Tony believed that in 1917, his grandfather came to New York from Sicily, hoping to earn money...

The truth, however, was far more complicated.

Antonino actually came here much earlier, along with his brother, on a ship that arrived in Boston in 1909... DANZA: Now, wait a minute.

So this... GATES: That's your grandfather Antonino.

DANZA: And it's 1909.

So, I'm off by a bunch of years then because I thought he came in 1917.

GATES: 1909, there it is.

Tony, you're looking at the moment that your grandfather, set foot in America for the very first time.

What's it like to see that and to see the ship?

DANZA: The ship is...

I mean it must have been just a luxurious journey.

Oh, my God.

GATES: And believe me they were not in the first-class cabin, right.

DANZA: Geeze.

It's amazing and it also pushes back the timeline for me.

You know, that's incredible.

GATES: Tony's "timeline" was probably off because his grandfather's life had been so difficult, so its details had not been passed on.

Records show that after Antonino arrived in Boston, he made his way to the industrial town of Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, where he found work as what was known as a "tinner."

It was a dreadful way to earn a living.

"tinners" spent their days in hot, noisy mills passing sheets of steel through vats of acid and molten metal.

Breathing in chemical fumes and earning abysmal pay.

DANZA: Imagine making that trip and hearing all these stories of paved with gold, the streets.

GATES: Statue of Liberty, 5th Avenue, Madison Avenue.

Then you go to Canonsburg.

DANZA: And be a tinner.

GATES: And you're a tinner.

DANZA: Well, you know, you feel like somebody sacrificed for you.

GATES: Oh, absolutely.

Yeah.

How do you think he was able to endure?

DANZA: I'm telling you, I just want to... (crying).

It's a lot to go through.

GATES: It is.

DANZA: You know what's funny is...

I never, uh, even considered, uh, liken a, a long heritage.

It never really entered my mind.

So, this, uh...

I don't know.

There's an effect on you, some kind of crazy, I don't know, gratefulness or something.

I don't know what to say.

Sorry.

GATES: No.

The affect is... DANZA: I think everybody should go through this.

GATES: I think everybody should.

You know, it's very powerful.

It's a very powerful experience and you know what, I have no idea why.

DANZA: Yeah, I don't know why tinner is striking me that way.

GATES: Yeah well, he was paying his dues, man.

He was working six days a week 10 hours a day.

DANZA: Yeah.

GATES: Despite his grueling job, Antonio tried to make a life for himself in America.

By 1914, he had married a fellow Italian immigrant, Tony's grandmother Anna Tummarello, and started a family.

But a great deal of tumult lay ahead.

Within a few years, the couple lost two of their children to disease and sometime around 1920, they decided to return to Sicily... Where they were soon reminded of why they'd left in the first place: poverty.

At the time, Sicily was among the poorest places in Europe and many struggled simply to put food on the table.

By 1929, Tony's grandparents were back on a ship, bound for New York, now with an even greater resolve, and many more children in tow... DANZA: This is my aunt Rose.

DANZA: "Melchiorre Camisa" now, oh Mike, yeah, my uncle Mike.

Anna Camisa and Francesca Camisa, age 2.

So my aunt Frances, my mother, my uncle Mike, my aunt Rose, my uncle Tony, and my uncle John.

GATES: They had five children born in Italy and then John was born in Canonsburg.

You ever seen that document before?

DANZA: No, no.

GATES: Isn't that cool?

DANZA: It's unbelievable.

GATES: In November of 1929, your grandparents returned to the United States with their six children, five of whom were born in Italy, including your mom, Anna.

DANZA: And how about, how about, so now you got these six kids... GATES: Yeah.

DANZA: And you've already been to America, wasn't an easy trip.

It's not going to be any easy trip to get back.

I mean, it just takes an enormous amount of gumption... GATES: Oh, absolutely.

DANZA: To get up and... Yeah, but I mean it's another one of those sacrifice things.

GATES: Oh, yeah.

DANZA: Where you do this for the kids.

GATES: Right, and for the future.

DANZA: For the future.

GATES: We soon discovered that Tony's grandparents weren't the only members of his family to make this kind of sacrifice.

Moving back just one generation, we found the passenger list for a ship that arrived in America from Naples on October 20, 1902.

Onboard were the parents of Tony's grandmother, Antonino Tummarello and Anna Caracci... GATES: Recognize those names?

DANZA: Yeah.

GATES: Those are your great-grandparents arriving in the United States from Italy for the very first time together in 1902 heading to New Orleans.

(stammering) DANZA: And I never heard this.

GATES: Your mother's parents were not your first maternal ancestors to try their luck in America.

Your great-grandparents came here first.

What's it like to find this out?

It's stunning.

DANZA: I had no idea.

I had no idea.

I thought I've always been so proud that I know that they got here and he's in, it wasn't true.

GATES: It wasn't true.

DANZA: Nothing I know is true.

Oh, my God.

GATES: Tony's great -grandparents were actually part of a very significant historical trend.

Between 1884 and 1924, a huge wave of Italian immigrants, roughly 300,000 people, moved to New Orleans looking for work.

Most were Sicilians, like Tony's ancestors and as newspapers from the era make clear, the work they found was often backbreaking... GATES: Tony, this was published in the Times-Democrat, a New Orleans daily newspaper on the 13 of July 1900.

This was about two years before the arrival of your great-grandparents.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

DANZA: "Italian Labor Rapidly Ousting the Sugar Belt Negroes.

Italian immigrants have driven out at least 75% of the Negro labor.

They are preferred to the Negroes for several reasons, chief of which are that they will work very cheap and are steady.

They will work right along all day Saturday and Sunday.

Their endurance is phenomenal."

That's just... GATES: In the late 19th century, I mean, go figure, right.

DANZA: But professor...

I'm trying to think how you could be cheaper.

GATES: People out of slavery for thirty-five years.

DANZA: That's what I'm trying to say.

What the heck?

GATES: I know.

Can you imagine how hard things must have been in Sicily to cross the ocean to work on a Louisiana sugar plantation?

DANZA: No, I do know that my mother told me that they were starving.

GATES: Oh, yeah.

DANZA: It wasn't even about livelihood.

It was about eating.

GATES: Perhaps unsurprisingly, Tony's great-grandparents did not stay in New Orleans...

Instead, they seem to have followed an itinerant path over the next decade, before ultimately settling back in their native Sicily.

Migration patterns like this were not uncommon at the time.

Many Italians who crossed the Atlantic later returned to their homelands.

Historians have dubbed these people "birds of passage" and Tony's great-grandparents are prime examples...

Causing Tony to reconsider, yet again, his family's story.

DANZA: Wow.

GATES: Nobody ever talks about this in our school books, but 70% of the Italians in that period did that.

They went back and forth.

DANZA: They were like migrant workers.

GATES: They were like migrant workers.

DANZA: Only thing is they had to go across an ocean.

GATES: Yeah.

Isn't that amazing?

DANZA: What people will do to survive.

GATES: Do you feel a connection to these people?

DANZA: I'm grateful.

I just feel this tremendous gratefulness, but I'm also sort of in awe of them as far as the way they not only persevered and hardships and tinner and the things, but this travel.

What were those journeys like?

GATES: What do you think they would have made of you?

DANZA: You know, when I went back to Sicily I was "the autore", "the cousin," "the cugino autore."

And they were very, very proud of me.

They were very proud of me, and I'd like to think that they would be proud of me.

I know they'd be proud of my kids, and I know they'd be happy that I'm continuing their line, I think.

GATES: Absolutely.

DANZA: But I am nothing compared to what these people have went through and accomplished.

GATES: We'd already traced Terry Crews' maternal roots back six generations, introducing him to ancestors who showed immense strength.

Now we had a more difficult task before us.

Terry's father was abusive and to explore his roots, we had to confront the fact that even Terry's happiest memories of him are tinged with sorrow.

CREWS: My father played the, the lottery.

Both legal and illegal.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: You know he played the numbers.

GATES: The numbers.

CREWS: So when he would hit was one of the most joyous times I'll ever remember in my household.

My father would hit and he would come home, he would wake us up, it would be like 1:00 AM.

We would always have pizza.

Cause that was the only food that was available at that time.

You know, he'd bring these pizzas, we'd smell, we'd be like, "Oh my God, pizza hurry."

You know, and we would flip out.

And my mother, of course, being very religious, gambling is not, gambling is not allowed unless you win.

My mother'd be like, "Oh my goodness.

We won."

I was like, "Wait, but...

Okay, I'm not even gonna answer that."

Uh, she'd come home and he would, he would have his jacket on and he would have all these clothes on and he would say, "Search my pockets."

GATES: Oh man.

CREWS: And my mother would go into this pocket and pull out a wad of money.

And then another pocket, another pocket.

GATES: Oh.

CREWS: And then... And then I would watch them kiss.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: And I remember saying, "This is just like on TV.

It's just like in the movies."

GATES: Right, right.

CREWS: It was, I was like, "That's my mother and that's my father."

GATES: Right.

CREWS: And they love each other.

GATES: Mmm-hmm.

CREWS: And we would just sit there.

We'd eat that pizza man, and... GATES: Yeah, yeah.

CREWS: We would just, it was just some of the best times I will ever remember, you know.

And I was like, "They love each other, look."

GATES: Yeah, mm-hmm.

They really do love each other.

CREWS: Look, they do.

You know because it was a lot of just...

It was so much fighting and so much stuff, but then those moments.

I said, "This is it, that's the ideal.

That's what I want our family to be all the time."

GATES: And then you go to sleep, it's like, "Okay, it's going to be a new day."

CREWS: That's right.

GATES: "Cause everything's gonna be better."

CREWS: That's exactly it.

GATES: And then, boom.

CREWS: It would go back.

GATES: There's no explaining away or excusing what Terry endured, but we soon encountered what seemed, at least, to be one factor that may have contributed to his father's behavior: Terry told me that his father was estranged from his father, Terry's grandfather, a man named Edward Crews... We found Edward in the archives of Calhoun county Georgia, marrying Terry's grandmother, Ermelle Smart, in November of 1943.

Ermelle is still alive today and Terry often visited her in Georgia when he was a child.

But he does not recall ever hearing her speak about Edward and as we began our research, the reason for that silence became clear... CREWS: "State of Georgia versus Edward Crews.

Style of case, abandonment.

State's witness, Ermelle Crews."

GATES: In 1954, eleven years after they were married, Ermelle sued Edward for the abandonment of their children.

CREWS: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Your father would've been about nine years old at the time.

CREWS: Mm-hmm.

Yeah, my, my father never said anything about this.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: My uncle Sonny, told me a little bit about the fact that, uh, he was not around...

He told me that he was in and out of their lives.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: And he would hardly ever showed up.

Um, so that would make the case for abandonment.

GATES: In June of 1954, Terry's grandfather pleaded guilty and was sentenced to one year at a public works camp.

He was discharged after serving about nine months, but his trouble with the law was just beginning.

Less than three years later, he was arrested again for trying to break into a liquor store, but this time, he did not get off lightly.

CREWS: "The State versus Edward Crews.

Plea of guilty to attempt at burglary whereupon it is considered and adjudged by the court that Edward Crews be placed and confined at hard labor in a chain gang, upon some public works for the term of 12 months.

March 29th, 1957."

CREWS: Hmm.

Not good.

GATES: And you've never heard anything about this?

CREWS: No.

GATES: And you've heard Sam Cooke's song "Working On A Chain Gang" 1,000 times, right?

CREWS: Uh, I mean, uh, I can go back in all the movies I've ever seen about this kinda stuff.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: And all I can say is, this, this stuff was real.

Like a chain gang.

GATES: Yeah, oh, and wearing stripes and it was horrible.

CREWS: Oh.

GATES: "Chain gangs" are part of a shameful chapter in American history.

They were a form of labor that evolved out of what was known as "convict leasing" a system developed after slavery whereby white businessmen could purchase prisoners to live and work under their control.

When that system was abolished in the early 1900s, chain gangs became commonplace across the Jim Crow south and played a major role in expanding the infrastructure of many southern states.

In practice, this meant that men like Terry's grandfather were essentially forced to work without pay, under inhumane conditions, as a punishment for even the most minor crimes.

CREWS: Well, it's, it's not rehabilitation.

Um, I'm sure, uh, they left a little bit more of their souls out there every day.

GATES: Oh, yeah.

CREWS: That's brutal.

Look at it.

GATES: Free labor.

CREWS: Free.

It's legalized slavery.

GATES: You got it.

CREWS: Wow.

GATES: And you know how hot it gets in Georgia?

CREWS: Oh, listen, man, that's all I remember about Georgia.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: As a kid, the heat.

It was unbearable.

There was times you couldn't even move.

GATES: How do you think having a father in and out of jail growing up, affected your father?

It could not have not affected your father.

CREWS: Yeah.

That, that right there had to be devastating to a nine, 10, 11-year-old boy.

Had to be horrifying.

GATES: Your uncle James told us that the bus route that he and your father took to get to school, passed by the prison where their father was locked up.

And that he and your dad would visit their father on Sundays.

CREWS: Oh.

GATES: And he would always promise to do better when he got out.

But as your uncle stated, he never kept his promise.

CREWS: This is so heartbreaking.

It's heartbreaking.

GATES: Edward Crews was discharged from prison on January the 7th 1958.

He was just 34 years old, but unfortunately, he had little time left to enjoy his freedom... CREWS: "Certificate of death.

Name, Edward Crews.

Date of death, March 5th, 1963.

Place of death, Butler County, Georgia.

Age, 38 years.

Cause of death, epileptic."

Epileptic seizure?

GATES: Yep.

CREWS: Wow.

GATES: Edward died of epilepsy when he was just 38 years old.

CREWS: Wow.

GATES: Your father was only 17 years old at the time.

CREWS: He was young, 38 years is young.

GATES: Oh, yeah.

CREWS: Wow.

Five years after he got out.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: Oh my goodness.

GATES: And you were born five years after your grandfather died.

CREWS: Yes.

I was, my father never talked about him.

GATES: Could you please turn the page?

CREWS: Oh my goodness.

Wow.

GATES: That's your grandfather's headstone.

CREWS: Whoa.

GATES: He's buried in St. Steven's Church Cemetery in Edison, Georgia.

CREWS: Oh my goodness.

"Edward Crews."

And this is in Edison?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

St. Steven's Cemetery.

CREWS: I've never seen it.

Never seen it.

I've been to Edison since I was a little kid.

GATES: Does learning these new details about your grandfather's life, do you think it will make you look at the relationship between you and your father with a new lens, you know?

With new perspective?

CREWS: Yeah, yeah, I mean, hurt people hurt people.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: And that's one thing I've learned in all my walks.

GATES: Mm-hmm, do you think that walking your father through your Book of Life is something you're gonna do?

CREWS: Definitely, I'm gonna invite my father out.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: And, we're gonna go over this book together.

GATES: But I'd have, your counselor standing by.

CREWS: Yeah, yeah.

No, I keep him on the speakerphone, like... Just chime in when I, when I need, when I need your help, sir.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for each of my guests.

It was time to show them their full family trees.

Now filled with ancestors whose names they'd never heard before.

DANZA: It's just magnificent.

GATES: Isn't that great?

DANZA: I appreciate it so much.

CREWS: This is like my own personal museum...

I feel them.

GATES: For each, it was a moment of wonder, providing a chance to reflect on the sacrifices made by generation after generation to lay the groundwork for their own success... DANZA: I just had the best parents.

I really just had the best parents.

But when you see this and you get to go back and see their parents' and their parents'-parents' and their parents'-parents'-parents' it blows your mind.

It blows your mind and it makes you feel, first of all, I can't get over the gratitude but really I do feel solid.

Like I have some kind of...

I have a history.

GATES: A foundation.

DANZA: A foundation, there you go.

GATES: Yeah, and you're standing on a foundation of ancestors.

DANZA: That's me.

CREWS: I'm actually connected to my past.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CREWS: And, I was never connected before today.

GATES: Hmm.

CREWS: There was a huge disconnection.

I just didn't know.

GATES: Hmm.

That's beautiful.

CREWS: You're anchoring me right now, man.

And when you look at all the worth that comes from being anchored, you know, I remember being jealous of white families in school and their fathers were the so-and-so's.

GATES: Oh, yeah.

CREWS: And I was like, "Wow," and they knew they could do whatever they wanted because they were a so-and-so.

GATES: Right.

CREWS: But we can do this too.

GATES: Yeah.

CREWS: I know I can do whatever I want to do, 'cause look how strong my family was.

GATES: Absolutely.

CREWS: I love that, I love that.

GATES: That's the end of our search for the ancestors of Terry Crews and Tony Danza.

Join me next time as we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots".

A Family, Torn Apart by Slavery, Reunites

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep6 | 1m 29s | Terry Crews learns an ancestral family was reunited after being sold off as slaves (1m 29s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep6 | 32s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. sits down with Terry Crews and Tony Danza (32s)

Terry Crews Discovers His Grandfather Abandoned His Family

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep6 | 52s | Terry Crews discovers that his grandmother sued his grandfather for abandonment. (52s)

Tony Danza 's Grandfather Endured Harsh Working Conditions

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep6 | 1m 45s | Tony Danza wells up with emotion while learning about his grandfather's grueling existence (1m 45s)

Tony Danza’s Greatest Audition

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep6 | 1m 30s | Tony Danza’s Greatest Audition (1m 30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: