July 25, 2025

7/25/2025 | 55m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Francis Collins; Mstyslav Chernov; Carly Ann York

Former NIH director Francis Collins discusses federal cuts to science and research programs and offers a warning. Mstyslav Chernov shares the raw experience on the frontlines of Ukraine's fight with Russia in his new doc "2000 Meters to Andriivka." Carly York explains how "silly science" has led to breakthroughs that impact our daily lives.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

July 25, 2025

7/25/2025 | 55m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Former NIH director Francis Collins discusses federal cuts to science and research programs and offers a warning. Mstyslav Chernov shares the raw experience on the frontlines of Ukraine's fight with Russia in his new doc "2000 Meters to Andriivka." Carly York explains how "silly science" has led to breakthroughs that impact our daily lives.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Amanpour and Company

Amanpour and Company is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Watch Amanpour and Company on PBS

PBS and WNET, in collaboration with CNN, launched Amanpour and Company in September 2018. The series features wide-ranging, in-depth conversations with global thought leaders and cultural influencers on issues impacting the world each day, from politics, business, technology and arts, to science and sports.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(dramatic music) - Hello everyone and welcome to Amanpour and Company.

Here's what's coming up.

Under attack in America, a warning from one of the country's most renowned scientists.

A long time director of the NIH, Dr. Francis Collins joins me.

Then.

(speaking in foreign language) 2,000 meters to Andriivka, a searing and unprecedented look at life on the front lines against Russia.

I speak to the filmmaker embedded with Ukrainian soldiers as they fight to save their lives and their country.

Plus, how did we get wind power?

How did we discover particle physics?

A focus on the more overlooked value of scientific research.

(dramatic music) Amanpour and Company is made possible by the Anderson Family Endowment, Jim Atwood and Leslie Williams, Candace King Weir, the Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poyta Programming Endowment to Fight Antisemitism, the Family Foundation of Layla and Mickey Strauss, Mark J. Bleschner, the Philemon M. D'Agostino Foundation, Seton J. Melvin, the Peter G. Peterson and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund, Charles Rosenblum, Koo and Patricia Yuen, Committed to Bridging Cultural Differences in Our Communities, Barbara Hope Zuckerberg, Jeffrey Katz and Beth Rogers.

And by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

- Welcome to the program, everyone.

I'm Christiane Amanpour in London.

There is fear in America for immigrants, for the press, for democracy, for financial stability and for the future of science and medicine.

In the first six months of his second term, Donald Trump has said about changing the very nature and fabric of America.

And in the crosshairs is science.

Unprecedented funding cuts and staff layoffs across universities, federal agencies and programs are threatening to derail research.

This is crucial in tackling the most pressing health issues facing Americans and indeed much of the world.

My first guest is sounding the alarm.

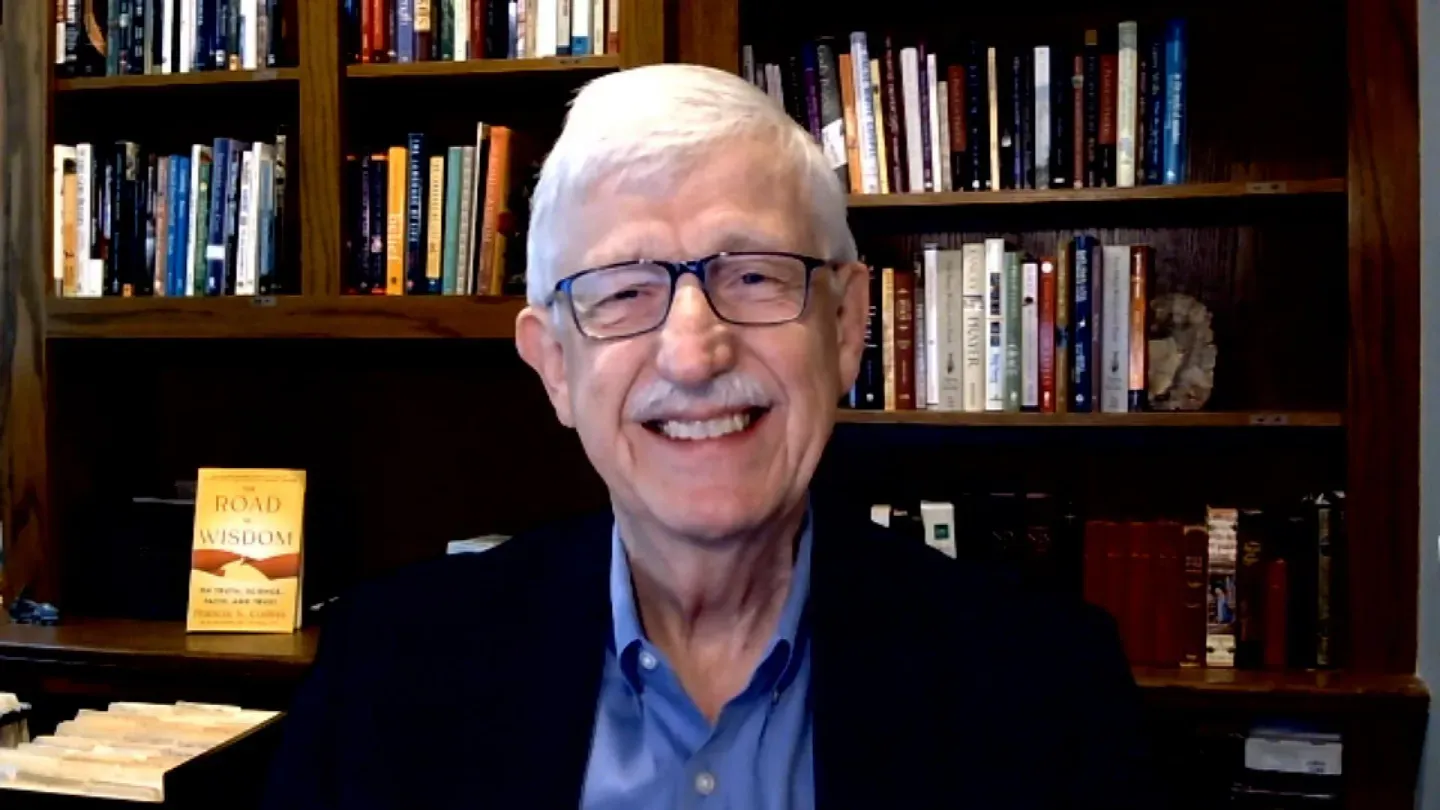

He is Francis Collins.

He's overseen some of the most revolutionary science of the last few decades.

He led the Human Genome Project and he was director of the National Institutes of Health where he served under three presidents and he led the agency's research on COVID-19 and the vaccine.

The NIH is the largest funder of biomedical research and has long had strong bipartisan support.

But under Trump 2.0, it has all been upended.

Dr. Collins announced his retirement in March saying his research was becoming untenable and he's here with a warning.

So Dr. Collins, welcome to the program.

- Thank you, Christiane.

It's nice to be with you and talk about something that I think is really important.

- I mean, so important, which is why we want you on the program to explain.

So you had in any event ended your term as head of the NIH.

You stepped down, I think in '21, but you were leading another lab and in the full daylight of the cuts and the threats by President Trump, you decided that you needed to leave, right?

You needed to resign or leave the NIH.

Just tell me what went in your thinking and why did you do that?

- It became untenable to continue to be there.

All kinds of restrictions were placed on the research we were trying to do.

You weren't allowed to order supplies.

You weren't allowed to start any new projects, only old things.

Staff were being fired with no justification whatsoever.

And we were also muzzled and told you're not allowed to speak even at a scientific meeting in any way because of concern that you might say something critical.

I felt distinctly unwelcome.

And it seemed as if if I was gonna have any useful role to play here, it would have to be outside of NIH.

- Just a personal question.

It must have been devastating for you as such a long time linchpin of the NIH and for your staff who you went to tell.

What was that last meeting like?

- Oh, Christiane, there were a lot of tears, including mine.

I've been there for 32 years I ran a lab the whole time I was at NIH, including during the Genome Project.

And when I was director, it was an amazing place with amazingly dedicated people.

And to have it come to this, I could not have imagined a circumstance like this.

And then there it was.

And yeah, there was a lot of heartbreak.

And there continues to be.

As we see this amazing engine for discovery that's been built over decades and has been the envy of the world, the way that NIH and its partners in the private sector and philanthropy have managed to make discoveries that are absolutely breathtaking, things I didn't think would happen in my lifetime.

And now it's being devastated by decisions made by individuals who seem not particularly interested in the consequences.

It's heartless, it's careless, and it's deeply damaging to something that I think all Americans would not want to see happening.

- No, I'm sure they wouldn't.

Healthcare is obviously a major topic for all Americans.

But I wanna then ask you, is this a scientific rationale or is it ideological?

How do you measure the rationale for these cuts?

- Well, some of it is ideological, but it's politically ideological.

2,500 grants at NIH have been terminated without really any serious explanation.

Some of them decisions made in minutes by somebody with no scientific training, simply by searching for key words that might be things they don't want to support.

Many of those grants were reviewed by peers of experts over many months before a decision was made about whether this was in the sort of top 20% of the ideas that come to NIH and then eliminated in two minutes by a non-scientist.

That's unimaginable at any time before now.

- So now tell me if you can, what exactly is the consequence of this?

What in terms of your research and the effect on people's health in the US and around the world?

- Well, there are immediate consequences for people who are depending on medical research to potentially come up with an answer to the circumstances they were facing.

I can tell you about Natalie Phelps, somebody who's in her 30s, afflicted with stage four colorectal cancer, who was on a pathway towards a clinical trial of immunotherapy at NIH, which she and many other people refer to as the National Institutes of Hope because that's what they need right now.

And because of staff cuts, that got slowed down.

By the time maybe she could have enrolled in it, she already had a metastasis to the brain and was no longer eligible.

So real consequences there.

I can tell you about young kids who have rare diseases who are counting on advances, which are happening right now at remarkable pace with things like CRISPR and gene editing, who basically their parents are wondering, is there gonna be anything happening now because they have been essentially slowed to a crawl by the cuts that have been made in that kind of research as well.

And people who are worried about Alzheimer's disease, as we all must as we get older, likewise, those grants also have been seriously slowed because of the attacks on universities where much of this research is done.

- There has been an attempt to go to the courts and to claw this back.

A federal judge in Boston last month ruled that the NIH had to restore some grant cuts on the basis of gender ideology or DEI.

Said the termination was illegal.

And the judge who was a Reagan appointee said, "I've sat on this bench now for 40 years.

I've never seen government racial discrimination like this."

What did he mean by racial discrimination and how do you have any hope that it will be restored under the new NIH director, for instance?

Because all of this happened before he was in place.

- That's very true.

So Dr. Bhattacharya is now presiding over an organization that I know he wants to flourish, but in a place where great harms have already been done.

I think the judge's comments related to the way in which any effort to understand diversity was now seen as unacceptable, which in many ways was eliminating efforts to understand health disparities.

Why is it that certain populations have a much less likelihood of living a full life without being stricken by disease?

We need to understand that.

And yet that falls under this same umbrella of DEI that is now considered a bad word in the current administration.

I gotta say, Christiane, the other thing that worries me about all this is what the long-term consequences are.

People don't realize that when a breakthrough happens, like the cure of sickle cell disease, which has now happened or the people with cystic fibrosis now can plan for retirement instead of an early death.

Those take years of painstaking work that is funded by the federal government before our company would ever get interested in something that might ultimately be a product.

There's all this basic science that has to get done.

The absolute mainstay of American success in that regard has been the way in which the federal government has invested in that kind of basic science through NIH.

And cutting that off means that the future breakthroughs that we all hope for are gonna be much less likely to happen.

- Dr. Collins, we just mentioned Dr. Bhattacharya, the new NIH head.

You and he had a bit of a go-to, you know, a bit of a contretemps, if I could put it that way, during COVID.

This is what he said about you to our colleague, to our colleague, Walter Isaacson.

- I've had now an opportunity to meet one-on-one with Francis Collins, and we've forgiven each other for, you know, whatever has happened.

So he called us fringe epidemiologists, and he called for a devastating takedown of the premises of the declaration, which then led to, like, death threats and all this kind of nasty stuff.

That was an abuse of power.

- Your reaction?

- Well, we have met, and we have basically agreed to try to move on from this.

I still strongly disagree with the premises of the Great Barrington Declaration.

I think that would have led to the deaths of tens of thousands of additional people from COVID.

But I regret the intemperate language that was used in an email, which was supposed to be private and which became public later on.

So let's put that part aside.

I don't really think that's an appropriate representation of what one tries to do as the director of the National Institutes of Health, to try to see what can you do to help people.

I'm not a politician.

I'm not power hungry.

I'm a scientist.

I'm a doctor.

I'm gonna try to help find those breakthroughs that everybody is counting on.

And it worries me deeply if something comes along that's going to get in the way of that.

And that feels like something that requires a response.

- You've said that you regret perhaps some of the communication that came from the podiums during COVID, that there was such certainty as opposed to admitting that actually this is an evolving situation.

Tell me about what you think you guys could have done better with 2020 hindsight.

- Yeah, with hindsight, I think in that crisis, when the information about the COVID virus was very incomplete, we did the best we could.

And I hope people will understand that was an honorable effort to try to share information that we thought would be most likely to save lives.

But it was often based upon incomplete evidence and it had to be changed later when we knew more about what was happening.

I just wish every time that somebody like me had been in front of a camera, we would have said at the outset, this is an evolving situation.

This is the best we can do right now, but it might have to be revised.

And then people wouldn't be so surprised when it did get changed later on.

I think we lost some of the confidence of the public because of those changes that were made.

And we maybe could have avoided that if we'd been more clear about the uncertainty part.

But Christiane, let me say, maybe 20% of the public, a loss of trust during COVID could be traced to some of those missteps that were made by the public communication efforts.

80% of it was done by all of the misinformation and disinformation that was being spread wildly across the internet, sometimes by politicians.

I've heard no apologies for that.

- Yeah, I wanna get to some of that, especially in the wake of the new Secretary of Health and Human Services and his essential dissing and dismantling of a vaccine program in the US and around the world.

But first I wanna ask you something that I'm not really, really on top of, this gain of function research.

President Trump has called it a dangerous research.

Others don't like it.

It was going on apparently in the Wuhan lab.

Tell me what are the pitfalls with that?

What are the facts and the pitfalls?

- Well, my goodness, there's a lot of confusion and noise about just even that terminology of gain of function, because in everyday usage, that's something that we consider actually a good thing.

When my daughter took piano lessons, I was hoping she would achieve a gain of function as a result.

But for things that we wanted to be very careful about, gain of function referred to when you're studying a pathogen that could cause human disease and doing things to it that might actually make it more pathogenic, that should only be done with extremely high justification under extremely careful conditions in a high security system.

And the US had a very careful set of plans that were developed over quite a few years about how to allow, if you were going to allow that, those very stringent circumstances.

So the system was in place.

Did the Wuhan Institute of Virology carry out any of those dangerous kinds of gain of function experiments?

They might have done so secretly.

The part that NIH was funding as part of a subcontract would not have allowed that because it would have been against those rules.

But it is so elevated this issue and caused a lot of understandable anxiety about, wait a minute, what's happening in those labs?

And now I think in an example of what feels like overreach, the government has now decided to stop a lot of research, including some very valuable things on tuberculosis, for instance, because it falls under the same label.

And there were very careful recommendations made about this in the past.

At the moment, they've kind of been pushed aside by a sweeping prohibition against research, which might actually be things we really wanna know and doesn't carry the same kind of risk.

- And Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is a known vaccine skeptic.

And no matter what he told his confirmation hearings, he's done things that he said he wouldn't do.

He sidelined the expert panel at the CDC.

He's pulled U.S. funding, or he says he will, out of the Gavi program, which is vaccines for internationals and people, you know, the poorest of the poor.

What is this going to do?

This kind of ideology and non-scientific approach to what it's going to do to America and actually to the rest of the world.

- Well, when you mix politics and science, you just get politics.

I'm afraid it's the circumstance we're seeing right now in the United States.

And certainly when it comes to vaccines, which have saved tens of millions of lives, hundreds of millions of lives globally over time, to have this put into a circumstance of casting so much doubt about the efficacy of vaccines is heartbreaking and dangerous.

Look what's happening right now in our country with measles.

We have the highest level of cases of measles in 33 years because of the reduction in vaccine receptivity in certain communities.

And that is not being helped by a government that seems to suggest that maybe these vaccines are not safe after all.

And basically, I think all of us are pretty distraught to see the dismantling of the oversight process of ACIP, which has now had its members dismissed and new members put forward.

Love to see the conflict of interest statements from those new members, which have not yet been released 'cause many of them do seem to come at this with a less than objective perspective.

And that's not what you need.

You want the absolutely most rigorous data.

You know, my book, "The Road to Wisdom" talks about this.

Have we begun to slip away from a dependence on objective truth?

Do we believe that that matters?

It almost seems as if people are allowed to reject facts that they don't like.

- Yes, well, Dr. Collins, welcome to our world as well.

It's terrible how disinformation and selective truths have affected journalism as well.

But I want to ask you finally, it's crazy from an administration that brought Operation Warp Speed and brought the vaccines that saved so many people during COVID, that was the Trump administration.

So how does it make you feel that the Trump 2.0 cuts is essentially causing a brain drain amongst your greatest scientists and, or your young scientists rather.

How does that make you feel as a patrician doctor and scientist when what do the young people say to you?

What do you say to them?

- They're deeply demoralized.

I talk a lot to young scientists right now as sort of a mentor.

And sometimes it feels like therapy because they are deeply troubled about whether there's a future for them in the United States.

Most universities now under attack have stopped creating new faculty positions or hiring postdocs.

And so people don't know if there's any place for them to go.

Many young people, as many as two thirds in one poll I saw are considering leaving the United States to go somewhere else like the UK or Europe or Australia, or if they speak other languages, other countries because they see a better chance there.

That is just astounding, like horrible to contemplate.

The United States has benefited so much in the last half a century by being the place where everybody wanted to come because this is where the greatest science was gonna happen.

And you'll be able to live out your dreams and make those next breakthroughs.

The politics has found its way in there.

And politics has to have winners and losers.

When it comes to medical research and health, everybody loses if that's cut.

The only winners, frankly, Christiane, are gonna be China.

'Cause after all, they've been trying to out-compete the US in the last several years in biomedical research.

They probably can't believe their luck right now.

- Thank you so much, Dr. Francis Collins.

- Thank you, Christiane.

- In Ukraine this week, protests amid growing outrage over President Zelensky's decision to target anti-corruption agency.

He now appears to be backtracking.

And every night now in Kiev and other Ukrainian cities, people are fighting to stay alive under a barrage of Russian missiles and drones.

But for the men and women under arms, the situation is even more dire, while also caught up in the on again, off again weapons supplies from the United States.

And a powerful new documentary shows the whole stark reality of life on the front line.

Mstislav Chernov's "2,000 Meters to Andriivka" was filmed during what turned out to be Ukraine's failed counteroffensive of 2023.

(dramatic music) (speaking in foreign language) His Oscar winning film, "20 Days in Mariupol" earned international acclaim.

I sat down with Chernov to discuss his experience embedded with the Ukrainian platoon on their harrowing mission.

Here's our conversation.

Mstislav Chernov, welcome back to our program.

Here you have made yet another magnificent film, really gritty, you can really feel, because you were, what's going on on the battlefield.

How did you get so close to these soldiers?

Because it's really difficult for any of us to get to the front lines.

- Yeah, you go to your friends, you go to people you've known for years, and then again, it doesn't mean that immediately you will be making a film.

Here I was already looking for a story that could make a film.

And so it would be a story that would represent the experience of all the soldiers on the front line, not only on 2023 front line, which was important back then, but also maybe 100 years ago, or 100 years later, or two years later, like where we are now.

And I was looking for that universal story.

And I found that little platoon that was at the time fighting for the village, and just looking at the map, looking at that strip of forest surrounded by landmines and the tiny village in the end of it as a goal, I saw that there is a film, there is a story that will symbolize just more than.

- So, I didn't really realize till the end, and I saw the credits, that a lot of the video, a lot of the footage is from the actual soldiers' helmet cameras.

And I'm like, "Oh my God, how did he get so close?

What is he doing?

I can hear breathing.

Is it Mstislav breathing?

No, it's the soldiers."

What was it like?

I mean, how close were you?

What was it like?

'Cause it just looks so awful.

- When we started working on this story, when I started looking through the footage that Platoon, the brigade has shot through their body cam footage for the battlefield analysis purposes, they do that all the time, and for their own YouTube channels, 'cause that's what they do now, I was thinking how to put that all together into one story, how to connect that, how to tell the story of those three months that they were trying to reach Andriivka.

And so, the only way I saw it could be done is to actually embark on a journey with them and to walk with them through that forest, through that 2,000 meters they were fighting through until the end, until their final goal.

And so, you see in the film, you see two storylines.

One storyline is Fedya, the protagonist, who is carrying the flag to raise over the liberated village, and on the way, we keep talking to some of his platoon soldiers, just human talk, nothing big, but that's what connects people together, talking about wives, talking about cigarettes, talking about universities, we have a rivalry in our university.

So, connecting audience to those human stories, and while doing so, we flash back into months and months of fighting to tell how that was going, that battle was going.

- So, I want to play this sound, you're talking about wives and personal lives, and the banality of life, really.

So, there's one of the soldiers who's called Shiva.

He was, I believe, he had a good position in the military police or in the Ukrainian police, and he left it to go to the counter-offensive.

And you were asking about it, and here's what he said.

(speaking in foreign language) - I almost smiled there, because I could see that this is just an ordinary man who's thinking about ordinary things, and yet he and the others are called to do extraordinary, extraordinary things.

And it just showed the clash between what's actually demanded of everybody in Ukraine right now, in a nation that doesn't really have a conscription, that people, a lot of them are volunteers.

- Yeah, exactly, they're not called, all the men you see on screen in this film have volunteered and went there to protect their land, the land that I call home, the land of my childhood, the mutilated, destroyed forests and fields and cities.

They go and liberate and protect them.

And you see that they're not, we keep talking about them abstractly as soldiers, with soldier casualties, but they're actually just civilians who made a decision and went to fight so their children will not need to fight.

And when I'm listening all the very important talks, international politicians arguing what Ukraine has to do, what Ukraine has to give up to achieve peace, or what are the casualties daily, what is the Russian gains or losses in land, all this is so abstract.

I know you know that is not just numbers because you've been there.

And I know too, because I am there all the time, but I want that experience, that reality to be in the rooms and in cinemas, on the screens, to shorten that distance between abstract talk and what's really going on.

Even if you're in Kiev, certainly not now because it's being bombarded, but when this was shot in 2023, it was the counter offensive, there was a certain calm in the capital and the big cities.

And the bloodletting was right there in Andriivka and the other villages and towns on the Eastern front.

So I want to ask you, because Shiva, to me, he was quite down.

He didn't see the way out, really.

He said, "Don't treat me like a hero.

"I haven't done anything.

"I've just come here.

"I don't want medals or praise or whatever."

But Fedya, who's the leader of this platoon, who, as you said, was carrying the flag to try to, well, he did raise it over Andriivka.

Fedya says that he's optimistic.

He says, "I think that war is probably the best time in life "to just start everything from scratch."

Because you're talking about the destruction in the forest, even the forest is destroyed.

I mean, how they thought they could get any cover from that forest, I have no idea.

But he was actually quite optimistic.

- That relentless optimism is why Ukraine is still standing.

And that's why I know that my city of Kharkiv and the region where it is and all other cities of Ukraine are, until people like Fedya are on the front line, until they know that they have to carry those flags, those symbols in them, until they are that optimistic and carry that resolve within them.

And no, I am safe.

We are all safe.

Because tomorrow, the world might turn away and be busy with other conflict, other war.

Someone will have different political agenda.

And what we learned is that the only person you can rely on in a war for your survival is just right next to you.

And we are alive and we still have our homes because men like Fedya.

- Now, some of them who you followed did not survive.

Some of them survived this battle, but not a following battle.

One of them didn't even survive this battle.

And you do a really poignant, poignant filming of his Gagarin, of his funeral, and his mother who says, you know, they say whatever they say, but it's our heroes who are being killed.

And the people who are not being killed are the people who won't get up and go to the front.

And it was a very poignant message from the mother of her dead son.

And I wonder, that was 2023, and in the interim, the world has got distracted.

There are wars elsewhere.

There's a terrible war in Gaza.

There is a different political reality.

There's a different president in the United States.

The idea of defending Ukraine has, you know, become much, much less certain.

What are people thinking in Ukraine now when they think that this war is still going on, that counteroffensive didn't do kind of what they hoped it would do, and they're not sure?

- I think we are, from far, it's almost easy to think about, again, to more abstract ideas of what people think or what their vision of future is.

What I really know is that, first, Ukrainians want peace.

That's what I see.

Those men who we see in the film, the same men that are still fighting, they all want peace.

But what they are not doing is surrendering, because they know that surrender equals death.

Their existence and existence of their families depends on how firm they are.

So there is, of course, everyone's tired, but at the same time, there is not less courage or less resolve in that.

I remember a reaction of Fedya and his platoon to the scene that happened in the White House.

And we spoke about that, and he said, "Look, I knew we are screwed.

"I knew things are gonna go bad, "but at the same time, I know that this is what's real, "and there is a clear goal of survival, "and then we're all gonna get united, "and we're all gonna get through this."

So worse things are, more realistic we'll become.

And more realistic we'll become, less illusions we have about what's gonna happen in the future.

Better it is for the nation.

And that's what I think is this film about, is about relying on you, and about defending what you see in front of you.

- It must have been quite something for you to see the raising of the flag.

Fedya figured out how to raise it on a ruin, basically.

- That village did not exist, and there was no place to put the flag.

And it was sad, but at the same time, I realized that this was exactly what we thought, that that flag was a symbol.

And that victory, a small victory, was a symbol.

And you can destroy a city, but you can't destroy a symbol.

- And yet, just a few months after this whole filming, and the liberation, Ukraine actually had to surrender Andriivka back to Russia.

And it happened at the time when the US Congress had frozen the pipeline of aid.

Biden was president at the time, and here's what he said when he was speaking, it happened to be from his vacation home in Delaware, about this.

- Look, the Ukrainian people fought so bravely and heroically, they put so much on the line.

And the idea that now, if you run out of ammunition and walk away, I find it absurd, I find it unethical, I find it just contrary to everything we are as a country.

- Do you think that cost, do the soldiers think that cost them the ability to fight properly and maybe be able to end this war, at least be able to go seriously to negotiations?

- Well, it definitely, that aid would definitely help to protect civilians from the invasion.

Because again, this is not, even when we talk about liberation of these villages or cities, we're talking about Ukrainian civilian population coming back to their homes.

So it is self-defense.

And of course, if a person who's trying to defend himself or herself does not have a weapon to do so, that is very sad.

But at the same time, it doesn't mean that that person will stop defending.

And I just, again, I was talking to Fedya and his platoon and his brigades, and they're outside of Izum, a city that was already occupied by Russia once.

And every Izum residents remembers the forest where hundreds of bodies lie in mass graves.

The people were killed by Russia during the occupation.

And they know that until Fedya and his platoon and his brigade are outside Izum defending, they are safe.

The residents of Izum are safe.

And therefore the residents of Kharkiv, my hometown, are safe.

And they know it's not about US, it's not about UK or Europe.

It's about that platoon of that brigade.

- I wanna end with playing actually a little bit of what you said in voiceover in the film.

Let's just play this.

- The village is 2000 meters ahead.

35 seconds for a mortar shell to fly.

A two minute drive, a 10 minute run.

But here time doesn't matter.

Distance does.

And it's measured by pauses between the explosions.

- I find that you are very calm and rational in your delivery and you say things that are actually really very meaningful.

But at the same time, we're seeing overhead footage of, as you say, this forest littered with bodies still.

I mean, littered.

And you really see the cost of what this war is.

And I just wonder how much longer you think anybody can tolerate it.

- Well, if you're fighting for your survival, you will tolerate it until you're safe.

And especially if you're fighting for survival of your family.

Right there, after those words that you just cited, after those words, I have a conversation with a young man with the name Freak.

And then he says his hometown is near Pokrovsk.

And right now is under threat of being occupied.

And it's very, very clear why those men are fighting.

I think this film is so timely right now because it just reminds people of motivation, of the reality of motivation of Ukrainian civilians and soldiers and volunteers and medics and journalists, why they're there.

And that they do have an agency.

We can't just be talking about them as they're far and abstract as their children that can't decide for themselves what to do.

They are the ones who make those decisions.

- Well, it's really powerful and you make great films.

Mstislav Chernov, thank you very much.

- Thank you.

- And the film "2000 Meters to Andriivka" opens in New York today and in cinemas here in the UK and in Ireland from August 1st.

Now, continuing our look at the importance of science and our next guest has just written a book explaining how the most curious and they're often silly research can lead to crucial breakthroughs.

"The Salmon Cannon and the Levitating Frog and Other Serious Discoveries of Silly Science" is by Carly Ann York.

Here now with Michelle Martin.

Professor Carly York, thank you so much for joining us.

- Thank you so much for having me.

- So, the focus of your book is stories that I bet a lot of people have actually heard about.

Research studies that they have been told were ridiculous and you pointed out the ways in which they were not or the ways in which basic research has actually yielded some really important discoveries that may not have seemed important at the time, but yielded tremendous benefits.

What gave you the idea for this?

- Well, the idea of this book really stemmed from my own research as a scientist and my experiences in talking with people about the value of my research.

I used to not do a great job of explaining why I did what I did and the value of my work.

And honestly, the reason I sat down to write this book was because I knew I had to get a better answer.

And so this is my thesis to the question of why curiosity-driven research matters.

You almost have too many examples in the book to name and some of them are actually quite hilarious and moving.

I think a lot of people remember the longtime Democratic Senator from Wisconsin, William Proxmire, who started something called the Golden Fleece Awards.

And one of the stories that you tell is about a grant to a Dr. Ronald Hutchinson.

What was Dr. Hutchinson studying and why did William Proxmire think it was ridiculous?

In this particular case, he was looking at monkeys and clenching teeth and that had direct medical implications but it was also the kind of research that is easy to twist around.

If you wanna make it sound silly, you can make it sound really silly and that's what Senator Proxmire did in this situation.

So he was studying aggression, specifically jaw clenching in rats, monkeys, and humans.

And so in 1975, as you write, he used Hutchinson's research in his second example of wasted federal funds.

And he wrote a scathing press release, as you said, the funding of this nonsense makes me almost angry enough to scream and kick or even clench my jaw.

And he said, in fact, the good doctor has made a fortune from his monkeys and in the process made a monkey out of the American taxpayer.

So Hutchinson experienced some really dire consequences from this, what happened to him?

- His research funding was stripped from him.

He had fellowships stripped from him.

It became his personal, like having his fire insurance canceled.

So he took a real personal hit because of this.

And I think it left a really lasting impression on the scientific community.

- Well, he got threats too apparently and all of his staff was laid off and all of his research.

Here's the part that really surprised me.

He actually sued Proxmire and his case went all the way to the Supreme Court and he won.

- He did.

- And what was the relevance of his research?

- This research, this is about tension and aggression and how we deal with emotions.

And we use animal models often to study very human things.

So by looking at things like jaw clenching in monkeys, we can extrapolate that to what we might be seeing in humans as well with both tension and aggression.

So it's not a far step at all to see how this could be really useful research.

- Give us another example.

Maybe you could do the one about, the title of your book is "The Salmon Cannon and the Levitating Frog."

What about the levitating frog?

The levitating frog example, tell us about that.

- So that came from the lab of a Nobel Prize winner, actually, Andre Geim.

And he had what he called Friday night experiments where the goal was to go into the lab on Friday nights and really just like goof off in the lab and try things with zero expectations.

So this levitating frog came from a Friday night experiment.

He was working with these big electromagnets and he poured water into the machine, which he did later say was probably not a great idea, but he saw that there were the water, it levitated, it floated.

So once he saw that, he was like, "Well, what else can we get that we can levitate?"

And they tried a number of different things, including pizza.

And then they went down the hall and they borrowed this little frog from biology and they levitated the frog.

So that was the first time that that had been done.

That's the first time that they had electromagnets that were strong enough to levitate something as large as a frog.

And this can be useful because it provides a microgravity environment without having to leave Earth.

So you can do a whole lot in terms of studying what might be happening in space to different bodies without the expense of actually having to send them space.

- Or the risk, frankly, of sending somebody to space.

So the whole point of all of this is to explain the value of basic research.

So for people who aren't familiar with that term, what does basic research mean?

- Basic research is simply curiosity-driven research.

So it stands opposed to applied research, which has a really specific goal to solve a problem or to create a product of some kind.

Basic research, on the other hand, has no goals whatsoever except to obtain knowledge.

So there will be no product at the end of a curiosity-driven research project, at least not immediately.

Maybe decades down the road, that information will become really useful for something else, but that was never the intention behind the research.

- And has the United States been a mecca for basic research, at least up to this point?

- Yeah, so the NSF was created in 1950.

- The National Science Foundation.

- Yes, and the whole goal of that foundation was to support curiosity-driven research.

And the reason why they wanted to support this kind of research is because it had been underfunded up until that point.

The US hadn't done a whole lot of basic research.

They relied more on European scientists, and they actually thought that that was a national threat to not be doing our own basic research.

So the idea was to create this foundation that would support curiosity-driven research, knowing that there might not be a product at the end of it.

Once we had the National Science Foundation in hand, we became the most innovative country in the world in terms of scientific progress.

We've had more Nobel Prize winners in the past five years than any other country.

So it has worked.

The goal of creating the NSF and supporting this kind of research has absolutely worked, and I hope we can keep funding it.

- Well, you know, your book arrives at an important moment.

As we are speaking, the Trump administration cut off nearly $2.6 billion in federal research grants to Harvard and is proposing to slash the National Science Foundation budget by more than half.

And it's just interesting because the administration is very keen to bring manufacturing back to the United States.

You know, their argument is that this is not just an economic threat to the stability of the country, it's a national security threat.

But if that's the case, it would seem that they would want to invest in basic research.

They would want to invest in education.

And yet, as we see, there's been an aggressive attack on particularly sort of elite universities, but also this funding for basic research.

How do you understand that?

- The only way that I can make it work in my own mind is to say that they must not understand the value of this because the value is huge.

And honestly, we're not even talking about a whole lot of money.

The NSF budget has been like $9 billion, and then compared to like new funds for ICE, which were 45 billion that just came out, it's a really small number.

And the payoff with that small number is huge in terms of innovation and being able to be leaders in science in the world.

So I cannot think of any logical reason why you would want to cut money out of the NSF.

And so I have to just tell myself they must not understand.

- So is this a problem of, that you don't, forgive me, you all as a group, as scientists, just have not done a good job of explaining why your work matters?

- Yes, in a lot of ways, absolutely.

So it's a complicated kind of a problem too.

For a long time, academia really actually frowned upon scientists taking time to talk with the public.

It's called the Carl Sagan effect actually, where the idea is if you spend a lot of time talking to the public and talking to media, then you are no longer a serious scientist.

- Oh, a popularizer, one of those, oh, okay.

I got it.

- Carl Sagan, he was nominated to be part of the National Academy of Sciences and he was ultimately denied it because he clearly could have done more research if he hadn't spent so much time on TV shows and books, et cetera.

So that kind of haunts academia a lot.

And it's changing for sure.

Now people are much more concerned about the broader impacts of their research and how it's affecting communities, but there still isn't really much formal training that's happening and real conversation about how to actually get this information to the public in the best possible ways.

- You know, you've made the point that people don't always make the connection between the research that's done, how the research was done, and the ultimate outcome.

What about drugs that a lot of people know right now, like Ozempic or Wegovy or GLP-1s, and things like that?

What's the origin story of those?

- Ozempic is a great example of this.

Ozempic actually came from studying the proteins within Gila monster venom.

So a Gila monster-- - Gila monster venom, okay, I got it.

- Gila monsters are, they're pretty big lizards.

They live out in the desert and they are venomous, but they also have this pretty cool ecology where they don't need to eat frequently.

And it turns out that one of the peptides in their venom is what allows them to keep their insulin levels nice and stable.

And it turns out that that is very similar to GLP-1, which is a peptide that is being used to help stabilize blood sugar in people.

Ozempic started for diabetes, and now it's being used for weight loss.

But there were decades between the time of identifying this peptide and realizing how it could potentially be useful and figuring out how to actually get it to work well and to get it to be accepted.

- So is that part of the problem here?

Is that people, some of these innovations take years to yield practical or commercial results?

- There was a study that was done that looked at the major drugs that are used in this country.

And the number is something like 80% of them ended up stemming back to some basic research question that had no intention of actually creating a medicine.

And the average time between that discovery and the creation of a drug was like 30 years.

So yeah, it's the long haul.

Support of basic research, it means you're gonna have to use your imagination and trust that this just building of knowledge is gonna ultimately pay off in the long run.

- If the federal government withdraws from basic research, is there any other entity that could fill that void?

- There are some private institutions.

I think that we are going to find a lot more stepping up soon.

The vast majority of basic research in this country is funded by the NSF, but I think scientists are finding now that perhaps we've become a little too reliant on government funding, especially when it is at the whims of political parties.

I think we're gonna have to diversify in order to stay resilient and sustainable as a discipline.

- You know, in the proposed budget, the National Science Foundation support would drop from more than 330,000 scientists, students, and teachers to just under 90,000.

What kind of real world consequences do you think that that might have?

- It's just huge.

It's like, it's immeasurable to think about that drop in the scientific workforce.

It'll affect everything.

It'll affect how innovative we can be with technology, with medicine, with our infrastructure.

I don't think there's any part of our lives that won't ultimately end up getting touched by that big of a hit.

- I wonder whether COVID has something to do with this.

I mean, there was a recent survey by the Pew Research Foundation that found that trust in scientists has fallen from 87% in 2020 to 76% in 2024.

And that is still a higher trust level than a lot of other professions, including journalism and Congress and things of that sort.

I mean, let's just be clear about that.

Nevertheless, that is a significant drop.

And I do wonder whether COVID had something to do with it.

What do you think?

- The way that I sort of saw that unfolding was science was happening in real time before the public's eyes.

And I think that that really pointed to some of our weaknesses in how we teach science.

When you're in high school, you walk into a lab and you're handed a list of instructions and all your materials are laid out there in front of you and you follow the directions.

If you do it right, you get some canned result.

And that's the science that most people know.

And the reality is it's very different from that when you're practicing science.

We don't get a list of instructions or materials.

We're figuring it all out as we go.

And there's a ton of trial and error.

And learning new information, it's part of the process, new information all the time, even if it contradicts former information.

For us, that's just the scientific process at play.

But to the public, it looked like we didn't know what we were doing.

And I understand why, but that's how the scientific process actually unfolds.

We need to just keep going and gaining all the information, even if it is contradictory.

And I think that the confusion comes down to how they think science should go versus how it really does.

- One of the things that I'm curious about is that as you've pointed out, is that the United States in the post-World War II era has led the world in basic research.

And I just wonder though, if the US retreats from basic research, where is that brilliance going to go?

Are they going to go back to Europe?

Are they going to go to Canada?

Are they gonna go to China?

- I think all of those are options.

I've seen a lot of initiatives in Europe calling towards graduate students in the US saying they will happily accept them and support them.

I personally have students who I have encouraged to apply abroad because things are just so tough here right now in graduate school.

So I think, yeah, I think China for sure.

And they're always at our tails when it comes to being the leaders of innovation and Europe as well.

But we're certainly gonna lose a ton of minds.

- Well, Professor Carly New York, thanks so much for talking with us.

- Thanks for having me.

- Given the era we are in right now, it's important never to forget the power and the integrity of science.

And that's it for our program tonight.

If you want to find out what's coming up on the show every night, sign up for our newsletter at pbs.org/amanpour.

Thanks for watching and goodbye from London.

(upbeat music) - "Amanpour & Company" is made possible by the Anderson Family Endowment, Jim Atwood and Leslie Williams, Candace King Weir, the Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poyta Programming Endowment to Fight Antisemitism, the Family Foundation of Layla and Mickey Strauss, Mark J. Bleschner, the Philemon M. D'Agostino Foundation, Seton J. Melvin, the Peter G. Peterson and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund, Charles Rosenblum, and by the members of the family of the late Dr. Michael Koo and Patricia Yuen, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities.

Barbara Hope Zuckerberg, Jeffrey Katz and Beth Rogers, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

(upbeat music) - You're watching PBS.

In Defense of “Silly Science:” How Curiosity-Driven Research Drives Discovery

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 7/25/2025 | 17m 53s | Carly York discusses her new book on discoveries born out of "silly science." (17m 53s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: